What Analysts Can Learn From Shadowserver’s “Italian Connection” Report

BLUF: The “Italian Connection” report from The Shadowserver Foundation is exemplary for its adherence to solid analytic tradecraft. The tradecraft is evident in the authors’ writing style, transparent methodologies, and use of structured analytic techniques. As analysts, we can learn from this report by similarly following the analytic standards that it demonstrates.

This weekend I read a report authored by Ned Moran and Ben Koehl at The Shadowserver Foundation. The report and associated IOC can be found via the Shadowserver blog post. This is one of the best reports I’ve read in a while as it demonstrates what I see as top-notch analytic tradecraft. I think there’s a lot that we analysts can learn by studying how this report was crafted.

These are the aspects of the report that are noteworthy for their adherence to solid analytic tradecraft:

The BLUF.

Transparent methodology.

The use of estimative language.

Clear prose; clear knowns and unknowns.

Use of a structured analytic technique.

BLUF

A BLUF or, “bottom line up-front” is used to quickly tell the reader what the report is about and what the conclusions of the report are. Intelligence consumers often do not have time to read lengthy reports and need to understand the “so what” in as little time as possible.

Within the first minute of reading this report, the authors present the context for the analysis and their conclusions. I do not have to read any farther to understand what the report is about or what the key assessments are.

Via the evidence presented within this paper we will demonstrate that at least two different exploit kits, or generators, were constructed by an unknown entity and shared amongst multiple operators believed to be located in China. We believe the following is a clear example of yet another ‘digital quartermaster’ of cyber espionage tools.

Transparent Methodology

The authors tell us what data they collected, how the collected it, and from that data, what they used as evidence to form the basis of their conclusions. The authors also provide us with the data they collected (via the IOC document). This transparency would allow other analysts to conduct the same research and draw their own conclusions.

What they collected…

For this research we set out to collect as many CVE-2015-5119 and CVE-2015-5122 exploits as possible. We excluded exploits that were delivered by popular crimeware kits such as Angler. We chose to focus our efforts on exploits used in a more targeted fashion by cyber espionage operators.

How they collected…

First, we crawled specific websites that have been previously used to deliver exploits and malware in ‘strategic web compromise (SWC)’ or ‘watering hole’ attacks4. Second, we deployed a variety of Yara signatures designed to detect malicious Flash files that exploited both CVE-2015-5119 and CVE-2015-5122…

The authors also tell us what evidence they used from their collected data to shape their analysis (e.g., ActionScript class names, compression algorithms used, Last-modified dates). They then tell us how they clustered the evidence which allowed them to identify relationships. There is no ambiguity about what data they used and how they used it.

This transparency makes for a defensible and more importantly, repeatable analysis.

Use of Estimative Language

The authors use estimative language throughout the report to communicate the varying levels of certainty in their judgements. They present scenarios as more or less likely based on the evidence at hand and also use if-then style statements to bolster their assessment (e.g., use of “unless”). Here are a couple of examples with my own emphasis added:

It is therefore unlikely that the files seen in the exp1_fla cluster were created via a shared exploit generator. A single generator would be unlikely to produce the differences seen in the underlying ActionScript. However, it is also doubtful that the above four underlying ActionScript classes seen in Table 9 would be identical unless the different operators were sharing code.

This data suggests that the APT20 and Unknown 17 actor were not sharing a generator tool. Rather, it appears that these actors were sharing exploit source code and modifying this code to suit their own individual needs. It is unlikely that a single generator would produce the differences seen in the underlying ActionScript. However, it is also unlikely that five of the underlying ActionScript classes would be identical unless the different operators were sharing code or tools.

Clear Prose; Clear Knowns and Unknowns

The authors assume the reader has a certain level of technical knowledge (cyber threat intelligence is, after all, an inherently technical field). But, they manage to write short, easy-to-understand sentences and avoid complex technical jargon. The prose and overall writing style make for a no-hassle read suitable for many audiences. Here is an example of three simple sentences that are direct and tell us important information.

Alternate compression algorithms are not a big change over the previously observed kits. However, remote payload retrieval is a significant difference. This new feature allows the SWF’s to be much smaller while also allowing the actors to switch out payloads on the server side over time.

The authors also explicitly state what they do not know, which is a critical intelligence practice. The unknowns that they present mostly have to do with attribution.

Although attribution was not our focus, we were able to conclusively attribute a number of malicious Flash files to different known cyber espionage operators. Where we were unsure regarding attribution we simply labeled the exploit to payload chain as ‘unknown’ followed by a number to distinguish between different sets of unknown activity.

And here, the authors tell us that they do not know with certainty what accounts for the relationships they identified.

While it is evident that independent operators are sharing exploit generators and code, the structure of these sharing relationships is unclear.

Use of a Structured Analytic Technique

What makes the overall analysis really great is that the authors chose to use a structured method: analysis of competing hypotheses (ACH). Structured analytic techniques help analysts to reach objective judgements by exposing biases, clarifying assumptions, and generally keeping the analyst “honest.”

The ACH method is the focal point of Richards Heuer’s Psychology of Intelligence Analysis and, as far as I can tell, remains a foundational technique for achieving solid tradecraft.

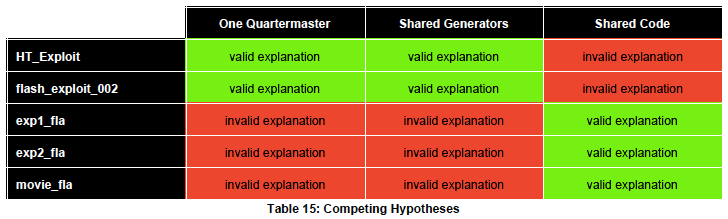

In this case, the authors present three plausible hypotheses. They then assess whether or not each “exploit cluster” is consistent or inconsistent with each of the three hypotheses. For instance, we can see that the authors believed that the third, fourth, and fifth exploit clusters were generally inconsistent with the “quartermaster” and “shared generators hypotheses” which might lead us to rule them out as valid explanations for the relationships across the clusters.

The value and benefits of ACH are very clearly articulated in Heuer’s book and so the application of ACH in this case is wonderful to see.